(An essay from Beauty and Pain by Amy Pleasant, RE: a collection of photographs by Swedish Artist Nathalia Edenmont.)

Roses rarest essence lives in the thorn.

Rumi

To look deeply at the work of Swedish-Russian photo-based artist Nathalia Edenmont is to see beyond the intrinsic beauty of the images. Her process is complex and dependent on a team of assistants to carefully build each garment under the artist's exact instruction. Each shot can take up to 18 hours to create one photograph, using a large format Sinar camera and a multitude of lenses. The artist recognizes that her work and life are intertwined and that she is compelled to create from this perspective.

At first glance, much of her work is full of wistful young women wearing ballgowns of spectacularly vibrant flowers and fruit. However, art is not always about what is readily seen, but more often about what lies beneath. If the bounty of nature serves as the metaphor of life in these images, a closer look at the covert and delicate details reveal a compulsion to wrestle with the nature of loss and death. In this work, death and life, pain and beauty are presented as flip sides of the same coin. This broad chronological collection of Edenmont's career becomes an intimate window into an artist's soul, a roadmap of loss and a testament to the resilience and courage of the artist.

Edenmont's work cannot be separated from her life experience. She displays an openness about the sweeping details of her own life, a life marked by significant losses. After the death of her mother, she found herself alone in the world (Yalta, former USSR) at the age of 14, becoming a ward of the state. She readily admits that her art is an extension of her personal process to carefully consign the pain outside of herself. Her work is markedly autobiographical, rooted in the primal grief of losing a mother at a most vulnerable time of life.

She tells the story of a childhood experience which indelibly set her on her artistic path. When she was 14, living in Russia, she attended the funeral of her best friend with the rest of her classmates. Her friend laid in an open casket dressed in a wedding dress as was the Russian custom for unmarried girls. She was puzzled when the teacher exclaimed for the whole class. “Look how beautiful she is.” The dissonance between beauty and death were too much for a young girl to understand in that moment. She reconsidered this, when two weeks later, her own mother died. Edenmont took great care to dress her mother in her most beautiful flowered dress and filled the room with flowers and music. She reflects, that from that day on, she formed the belief that, “There is no beauty without pain or pain without beauty and in her mind, they are the same.” This idea was cultivated into a philosophy which informed her art throughout her career.

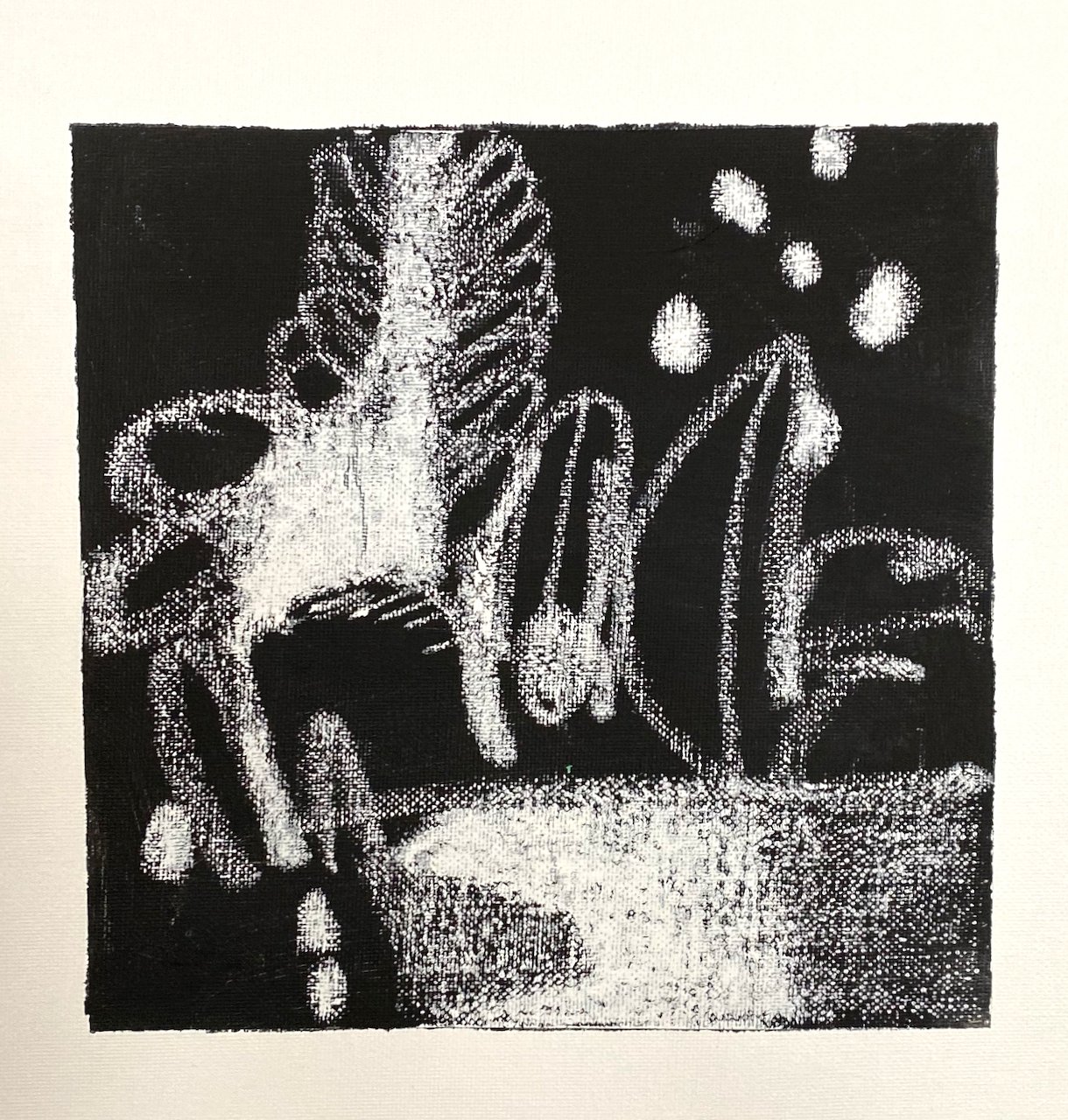

The first photographic series produced in 2007- 08 returns to that day, substituting dark, emotionally raw images with the memory of the flower filled room on the day of her mother's funeral . The stark images reveal the seeds of the journey of a young girl navigating a life alone. The seminal tableau

titled, Death is recognizable immediately as a deathbed scene. A wash of muted lifeless grays is broken by the copper red of mother and daughter, the artist herself playing the role of her dead mother. The daughter fully gazes at the viewer with both sadness and resignation. Edenmont also places herself underneath the gauze wrapping in a fetal position in Still Born, a metaphor for what death leaves in its wake to those left behind. A child's grief, marked by a great feeling of aloneness with the implication that the effects of such a loss have no expiration date. This thread continues in Family. This is the first use of a red haired body double who sits in oversized mourning clothes between two empty chairs. The girl is unable to move beyond the moment as the chairs sit on the skirt of the garment. A more explosive approach is evident in Lost, in which the portrait in red serves as the backdrop for the dead rabbit in the model's arms. This particular piece could be interpreted as a transition to a more stylistic approach and an incorporation of color and beautiful garment to serve as distractor from the gravity of the subject matter.

This metamorphosis is complete with a new series which continues thematic elements of death and grief through the lens of young women dressed in spectacularly beautiful floral ballgowns. The visual feast provides a diversion from the hard reality these images speak to. Flowers became her metaphor for both beauty and death. This focus on the fragility of life is perhaps best revealed in a seminal piece titled, Requiem. Taken on its own, it is a beautiful portrait of a young woman surrounded by a garment of flowers. But on closer inspection, Edenmont explains that the use of flowers is reminiscent of flowers piled upon a grave. The materials she chooses for the garment offer clues to the viewer of the embedded narrative. In Consciousness a young girl is clothed in Forget Me Nots. The hair upon her head is woven into a nest holding three dead birds giving the impression that they are a part of her. Four have fallen out of the nest onto her garment. In Grief, a nest containing dead birds is placed within the brilliant but dead foliage. The colorful vibrancy of Eden gives a false first impression in view of the dead insects embedded in gown. All of these ancillary details serve as a coded language implanted with the sting of loss, an acquiescence to the fragility of life and the finality of death.

Edenmont's walk through this world continued and her work followed as she turned to the personal and collective experience of coming of age as a woman in a misogynistic world. Once again, the first of the series is stark without embellishment of flower or fruit. Duty Free, one of 14 photographs of a young women's head wrapped in plastic cannot be mistaken for anything other than a calling out of a culture which treats women as objects. In Bouquet, this message was transformed by flowers in its portrayal of an asian woman who has morphed into a withered and decayed bouquet of flowers. These images, however, are not the last word. The artist flips the narrative with the snake like creature in Huntress and the emotionally withholding woman in A Rare Smile. On closer inspection of Excellence, the beautiful wedding dress made of toilet paper is a not too subtle commentary on marriage or more to the point, the end of a marriage. These women fuel their narrative and emanate power and are fully in control in gesture, expression and garment.

This thread continues as she turns her attention to the maternal, marking the confusing rite of passage for young girls in Devine and including a reinterpretation of the Eastern Orthodox Madonna icon in her Mother series. This pivot towards the maternal reaches a crescendo in her most recent series, Fruitfulness. The models once again serve as an armature, however, the floral motif of the garments is replaced with fruit. This body of work reflects her own struggle with the aftermath of a late term miscarriage and the resulting infertility. Once again, the art becomes a means of expression of the heartbreaking grief. The other models of this series (Juicy, My Mind's Eye,Prosperity, Dolce Vita) are dressed in a bounty of the most luscious radishes, carrots, grapes, tomatoes, strawberries and cabbages, a direct reflection of the fertility of the earth, all rooted in Mother Earth. The artist has portrayed what is painfully out of reach.

Memories of her childhood in Russia remind her that she was raised to believe in the importance of young women’s fertility and the oft-made comparison to a flower in full bloom. On the other end of that metaphor, women were described as “old potatoes” when they aged beyond their childbearing years. She explores this idea with a bit of irony in the piece, Propaganda, a self portrait which makes her seem larger than life surrounded by mounds of potatoes. Besides bringing a stereotype to life, she hints at the time in Russia when for two years they ate only potatoes for breakfast, lunch, and dinner in spite of the rosy economic outlook which the Soviet Union presented to the rest of the world. Her work serves as witness to her pain, yet an intention to imbue hopefulness is evident as well. The potatoes have new sprouts and the model’s youth speaks of renewal. In Edenmont's view, the power of the universe is on full display in the cycle of the seasons, from life to death, to life again and this perspective helps every thing make sense. As she observes, “Even old potatoes will yield new fruit.” When we are gone the worms will do their work and life begins again."

Now, Edenmont sees her life's body of work as her children. She is not the first artist to see the connection between art and soul. Her ideas are fully formed in her mind. She estimates that they number in the hundreds and each year she sifts through these images and focuses on the twenty to thirty which she says, “I can’t live without.” The intimate and personal nature of her work provides the scaffolding beneath the process. Few people are aware of the complex process behind these images and how all pieces must come together like clockwork for a successful conclusion. In her words, "I work in a bloody serious way. There are so many risks in each piece that I create. I am always thinking this may be the last one. I do my best like there may be no tomorrow." Her life experience lends to the notion that life is not beautiful in itself, however, she has done her best to remind the viewer of the beauty as well, to boldly lay the dark and the light next to each other.

She shares this kind of courage and honesty with the world through her person and her work. Without children or family, she sees her artwork as her legacy. She understands that her presence through her art will continue in books, galleries, and museums long after she is gone. It is her hope, that future generations can see that honesty and creativity can transform life’s pain into beauty.

by Amy Pleasant